First Caboose to Maverick

We go for a ride on a little train that thought it could...

Arizona Highways magazine, January, 1963, Page 5.

by Don Dedera. Photography, Darwin Van Campen

|

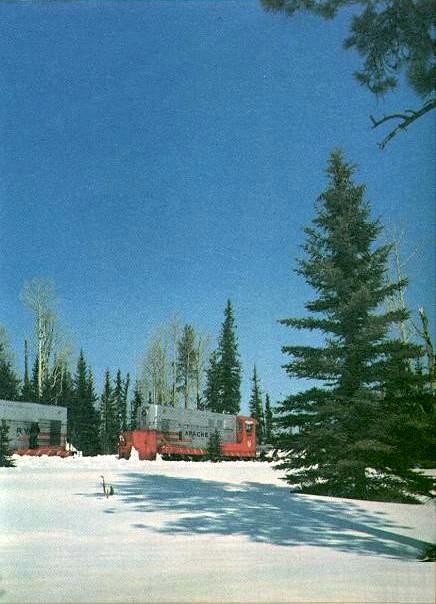

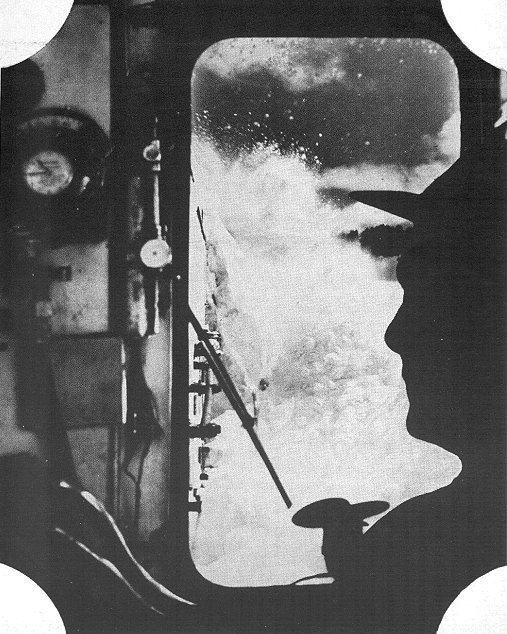

Snowbank ahead!

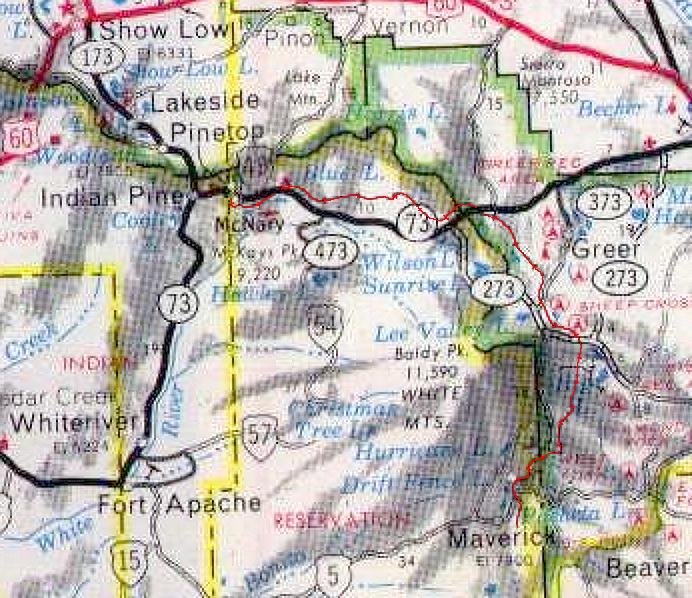

He was asked to jam two hundred forty tons irresistibly into an object of unpredictable mobility, and not break anything. With a puny sliver of steel, he was supposed to brush aside the biggest natural phenomenon of its sort in the memory of man. "Take the first caboose to Maverick," was the order from Mounes to Calhoon. Nearly every spring in the Whilte Mountains of Eastern Arizona a local agony begins with that command. It is a trialing time for the men and machinery of The Apache Railway Company, "Arizona's Longest Short-Line Railroad." The Apache is in two parts. Northward is a year-around milk-run, common carrier route to Holbrook and Snowflake, over which are hauled mostly the supplies and products of Southwest Forest Industries. But southward, to the logging camp of Maverick, is a ding-dong, double-decked, deep-dished doozy of a rail line. By air, Maverick is thirty-seven miles from McNary. By Apache Railway, it is sixty nine. The line never drops below 7,000 feet elevation. The rails knot around 16-degree bends, slash the bases of Arizona's second-tallest peaks, and overhang eternal granite canyons. Summertime fishermen know the White Mountains-a wide, wild, rolling killer country of frozen platinum cienegas and ebony

Destination -- Maverick!

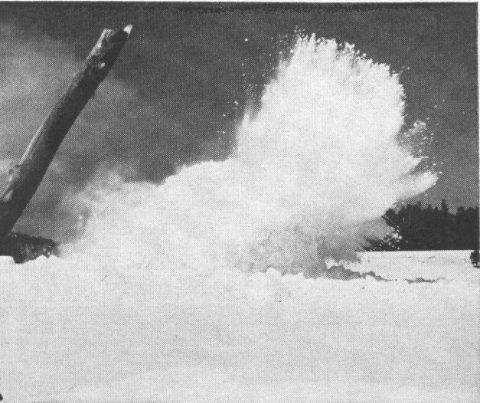

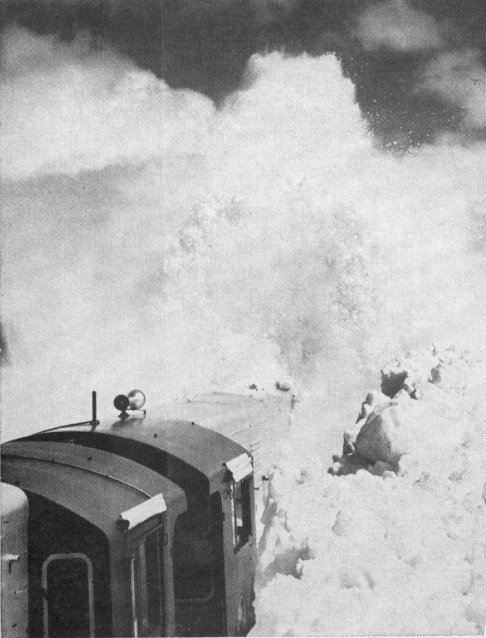

peaks of wandering fence posts along obliterated roads, of dagger winds and brooding clouds. In average years, logging goes on through the fall, and well into the new year before late storms block the summit of the Apache at 9,400 feet. The tracks may be closed only a few days or weeks. But last year. . . The oldest pioneer could not recall such a winter. In one month nearly 100 inches of snow fell at Maverick. Day-by-day depths were as much as 42 inches. In that month 52 inches fell at McNary, and one day the weatherman measured nearly a yard on the ground. Below in the agricultural valleys farmers rejoiced. The record snows promised the best irrigation storage in twenty years. But the snow was pure affliction for a little mountain railroad, especially in this year when the Maverick pine and fir and spruce were so urgently needed. Seldom had the lumber and mouldings mill at McNary been so short of sawlogs. The storage ponds held only a few water-logged sinkers. Several hundred McNary millhands gauged the supply, remembering 1958 when the logs ran out, and eighty men were laid off. And, too, a new paper mill at Snowflake awaited an increasing flow of wood pulp from the forests served by the Apache. Little wonder the ordeal of The Apache Railway caught the public fancy. Citizens of Arizona began to call the Breakthrough Special "The Little Train That Thinks It Can." With a grease-blackened glove, Nixon Calhoon massaged the sleep from his Irish green eyes and studied the tools of his trade. Marine veteran of Pacific invasions, Calhoon is shop foreman and engineer for The Apache. Before him loomed a pair of Fairbanks-Morse diesel locomotives rated at one thousand horsepower each. In the dim, vaulted railroad barn they seemed even taller than their fifteen feet. They showed the scars of hard work: gouges in the silver and red paint; chips in the Indian head emblem; hairline cracks in the cab windows; trails of the welding torch on the iron steps. Beneath their homely exterior the locomotives were trim and tuned, Calhoon knew. Over the winter he had bossed their overhaul. Two lean yards of man, Calhoon ducked in and out of the cabs and edged along the catwalks. He measured the levels of radiator water and crankcase oil. He checked the generators and air compressors. He circled the back-to-back engines, inspecting the running gear. He kicked the blunt red plow on Engine 200 and thumped the smaller plow on Engine 100. Satisfied, the engineer threw the battery switches and cut in the auxiliary fuel motors. He hit one starter button, then another. The engines cranked briefly and rumbled. Blue smoke perked upwards from the exhausts. Calhoon watched the dials-fuel pressure, lubricating oil, air pressure. He tested brakes. He glanced wordlessly at his section crew huddled in the other cab, at the shop workers, at his fireman and brakeman. The tall double doors of the McNary shops swung open. A dawn gale was driving snow horizontally across the dull gray town and yards. Ready? Calhoon wrinkled a brow. Ready, his brakeman waved. Calhoon jerked the horn cord twice, released the air and drew back the throttle handle. The train moved out through the yard switches, past the weathered cabins of millhands, by the tank towers, and up into the mountain blizzard. For twenty climbing miles Engines 100-200 cleaved the virgin snow with their plow, throwing a frosty spume. It was a train without a track, nosing into a white nowhere at fifteen miles per hour. Inside the cab, Brakeman Lindsey Neal flipped on the heater and windshield wipers, and plugged in the coffee pot. "Only railroad I heard of that provides coffee for the crews," he said. At Milepost 6 there were shadows of elk tracks, filling fast. At milepost 10, the clank of rocks hidden in the roadbed. And at Milepost 23, the Breakthrough Special shuddered into its first major barrier, a 600-foot-long cut filled with compacted snow. Drive motors whining, the train charged the cut. Chunks and spray exploded thirty feet high. The train slowed . . . and slowed . . . and stopped. A big bullet in a Bunyanesque cotton batten. An immense steel fist absorbed by an enormous down pillow. Faster than the wall of snow could seize the train in a frozen grip, Calhoon gunned the motors in reverse. "In other years we've gone through Twenty-three without slowing down," he said. With three hundred feet of running room, Calhoon opened the throttles for another forward rush at the wall of snow. In the last seconds he shut down the power, saving the drive motors, letting the locomotives coast toward collision. Crewmen caught their breath and screwed their eyes and braced against the firewall. "C-r-r-rump!"

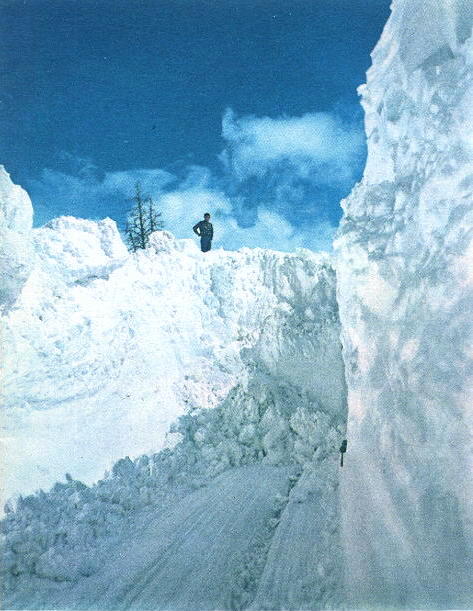

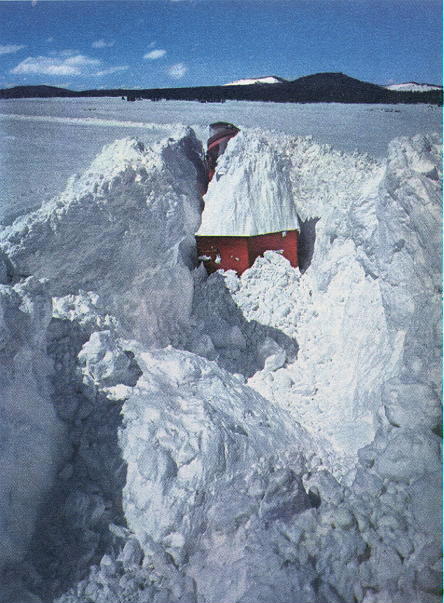

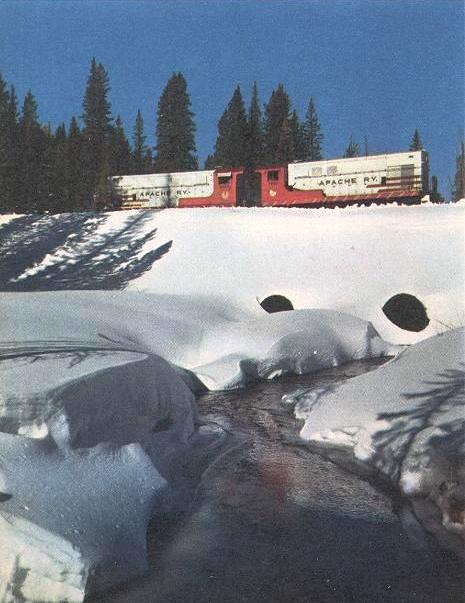

OPPOSITE PAGE

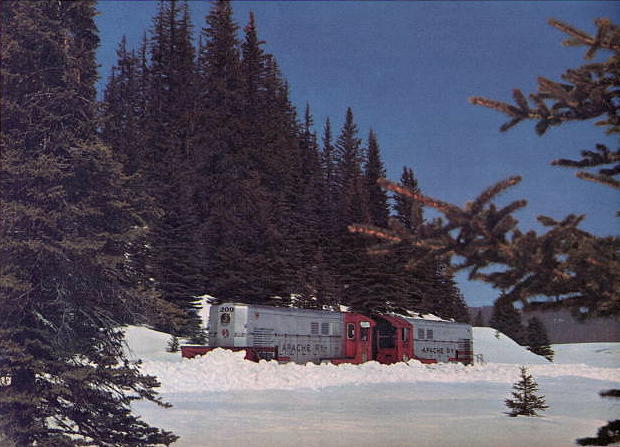

"The Cut At Mile Post 32"

"Fighting A Snow Barrier"

"Crossing the Little Colorado"

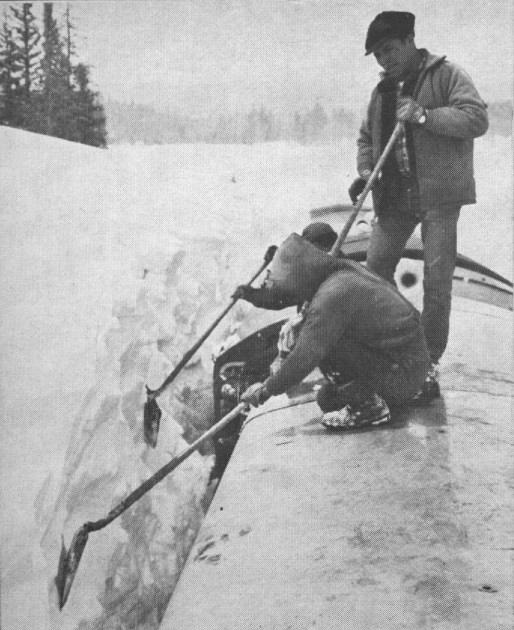

"Stopped For Repairs" Snow geysered up. Cracks ran out for fifty feet into the blanket of snow. Calhoon backed out for another running start. The locomotives gained four yards through Milepost 23. As one rugged old railroader said: "Sometimes it gives; sometimes we give. But it's the biggest thrill of your life if you don't land in the ditch." The danger of the ditch is real. Snow-hidden ice is the greatest threat to the Breakthrough Special. By vibration, by intuition, by experience, engineers must sense the icy shelves. Two blinks of bad judgement can put a train two days off the tracks. Again and again Calhoon battered the cut at Milepost 23. Snow piled over the blunt head of the lead engine and sloped down to the catwalks, covering the radiator shutters. Repeatedly the engines overheated, and the track crewmen shoveled clean the cooling system. When the engines cooled, the train went again into the cut. At times, car-sized snow cliffs hung in delicate balance above the cab windows. Charles Nez, Simon Padilla and Ramon Charley cut steps in the ice and pried off the draping deadfalls. By midafternoon the Breakthrough Special burst out of Milepost 23. The sky cleared for sunset and Calhoon grinned. For this day, the pressure was off. Back down the mountain retreated The Little Train That Thought It Could.

In the warm, relaxed atmosphere of the cab, the crewmen brought out their stories, some tall, some short, all about railroading. From the beginning The Apache has had its colorful moments. Every mule in the county, and one hundred fifty men, including a strawboss cousin to Geronimo, started construction in September, 1916. The grade was finished in time for the flu epidemic of October, 1917. Three men died. Steel was laid without ballast on the frozen earth that winter. The first car was delivered to the construction camp, later to be called McNary, on April 5, 1918. First off, the bank was robbed and the railroaders took chase. The robber fled into a rancher's ambush and acquired four fatal holes in chin and neck. Apache train crews have watched the White Mountain Indians progress from pole litters to pickup trucks. Nowadays, through old Apache strongholds, the McNary Rotary Club annually plays host to 750 passenger guests on a springtime ride to Maverick. That train always manages to stop for a flock of turkey hens and poults, at some point along the right-of-way.

OPPOSITE PAGE

"Hitting A Cut"

"Black River Crossing"

"We broke snow all the way out there, and found a bunch of guys that had gotten into the fishing concession. The sick man had a hangover. They didn't want to be rescued after all. Can you imagine calling out a train in this kind of stuff for nothing?" And what was the Apache's most exciting moment? Perhaps it was during the last war, when a flatcar missed a coupling in the mountains and spilled rails all along the road in a hundred mile-per-hour dash to McNary, where it whacked a string of log cars. Or maybe it was the heroism of Wesley W. Clark. After the engineer and brakeman jumped off a runaway train in 1949, Conductor Clark stayed aboard to stop it. But all hands agreed, there is nothing so dependable as a snow breakthrough for misfortune. In 1957, at Milepost 37, the breakthrough stalled when the main plow, made of half inch steel plate, was torn like a sardine can. The next year, at Milepost 23, the late John Benson was pinned in his engineer's seat out of reach of a racing throttle, when a snow avalanche spilled through the cab windows. Luckily a crewman in the other cab took command. Then there was the bad week of January 1962. The last train of the season was trapped in Milepost 37. A triple-header with twenty-five empty log cars and caboose could not drive forward or back up. The crew of Roy Holland, A. J. Stewart and Lew Calhoon, Nixon's dad, radioed for help. Snow weasels of the Navapache Electric Company, of the Apache sheriff, and of Ermon Lewis's radio service set out with food for the men and fuel for the locomotives, to prevent their freezing. Men of two of the weasels became lost and spent a night in a storm. Enough fuel reached the train to keep the engines idling until Lyle Smith, Maverick logging superintendant, arrived with bulldozers to dig the train out. The elder Calhoon and his crew spent sixty-five hours, from Sunday morning to Wednesday night, with the train. "Most of the time the wind was so bad a man couldn't breathe outside of the engine cab," said Calhoon. That was another day. Now the Breakthrough Special eased into its heated McNary barn. and the crew went home to supper and a few hours of sleep.

Ordinarily, S. E. Mounes would have been with his men, out in the snowfight. On other breakthroughs the executive vice president of the Apache has put on old clothes and joined the plow crews. It's been said of him -- he runs The Apache as a boy who found it under the Christmas tree. "Now, doggone it, I'm tied to this desk," he said. Sleet pecked on the window behind his desk in the paneled McNary headquarters. Mounes is thirty-five years a railroader, a graduate of the Illinois Central. "A hundred things keep me off that train," he continued. "The Apache has been going through a transition. It's growing from a railroad principally serving the lumber industry to one serving a diversified forest products industry. "That pulp plant at Snowflake means we now can put to beneficial use three-quarters of every tree cut.

Fighting the drifts!"

"We've had to more than double our transportation capacity, and more approach the qualifications of a Class No. 1 railroad, instead of the Class No. 2 that we are now. "We're thinking in new ways, ordering pulp cars converible into flats which can be put on the main lines off seasons. "We're upgrading track structure, Installing treated ties. Studying new freight rates, Hauling loads twice as heavy. Doubling our locomotive usage. "We're hauling diversified commodities to the mill -- such as liquid chlorine, salt cake, sulphur, lime, alum, resin. And of course we're hauling out the products of the mills. "All this, in addition to our historic lumbering freight, our four hundred cattle per year, our equipment and supplies, our brick, wire, feed, salt, fish hatchery food-- and, we even had two cars of black walnut logs from Fort Apache for export to Belgium for gun stocks. "That's the present, and for the future the Apache tribe has 155 million tons of iron ore blocked out just twenty-five miles from the paper mill. In anticipation of development of this resource, we've laid heavy rails. "At this time we're in the process of doubling capacity, adding ninety-five cars to bring rolling stock to two hundred. Our labor force is doubling. You can imagine what this means in the way of revising sheds and shops. "That's what is on my mind. "And every other minute I'm asking myself why I'm not out there fighting the snow."

The 1962 breakthrough began on a Monday. Tuesday was the first day of spring. As the Breakthrough Special climbed again into the mountains, a late, wet, windy storm came to stay in the White Mountains. "The first day of spring," said Conductor Roy Holland, "is not necessarily the first spring day." Under gunmetal skies the train cleaned out Milepost 23, and pushed on through alpine vistas. Like magic magnets, the hidden rails guided the train across open parks bordered by icy firs, pines and spruces, by leafless aspens guarding the brushy draws. The train passed Sheep Crossing on the Little Colorado River, where the snow covered picnic tables and campsites, and was level with the top of a hunter's abandoned house trailer. Barely protruding from a snowbank was a red octagonal highway sign. "STOP", it begged. On the train crawled to Milepost 32, a curve on a point of a hill. Once again sprays of snow slid up the plow, compacted and held. Nixon Calhoon rammed . . . and rammed. Tons of snow collapsed against the sides of the train, and a green stain oozed from the vicinity of the radiators. "Bent and broken," Calhoon observed, "We've got to go back to the barn." Wednesday was worse. When the battle resumed at dawn, the Breakthrough Special was thirty-six miles from Maverick. There was delay in loading bulldozers for the fight at Milepost 32. Then in the mountains one would not start, and new batteries were ordered from town. Once started, the bulldozers floundered in the drifts, and drivers Joe Magill and Jay Webb had to cable and winch each other out of endless bogs. And if that wasn't enough, the rear plow of the train was ruined on an ice wall. At the end of a tiring day, the Breakthrough Special was still thirty-six miles from Maverick. In the White Mountains old-timers say knee-high to a tall indian is a lot of snow.

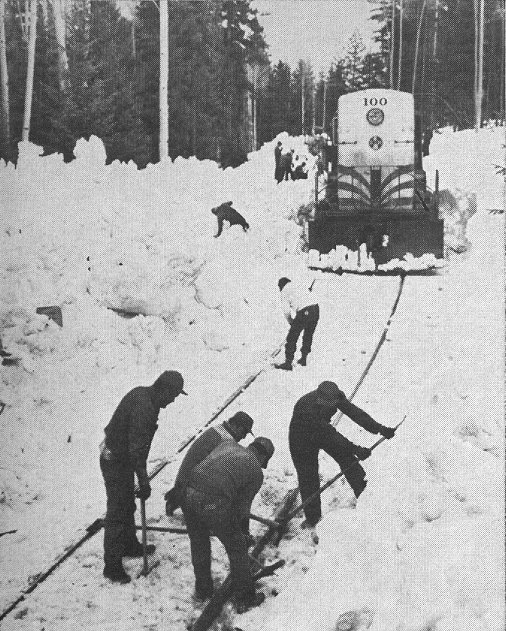

Scraping Snowdrift after Breakthrough

Realigning track after derailment! Charley Nez, foreman of the Brown Creek section, is a tall Indian. Once Wednesday he stood tiptoe on the top of the fifteen-foot-high locomotive, and reached up as high as he could with a shovel, and yet he could not touch the top of the snow drift. That--that was a powerful lot of snow. The dispirited crew was cheered by news at McNary. Lyle Smith with the Maverick bulldozers had opened a long section of the far end of the line. From the capital, Phoenix, was a message of another sort, on a greeting card decorated with purple pansies. The inscription was: "We think you have lots of courage--Little Train. Please be well by summertime so we can hear you say Hello at Sheep Crossing. We love your country up there, and try to visit for a while each year. Your friends, Bill, Marge, Ruth and Gale Kirsop." But Thursday was no better than Wednesday. The 'dozers dived early into Milepost 32, yet by nightfall the cut was still blocked. Friday brought fresh storms. Fearful of losing all cleared track, Mounes ordered out a night train to ply the freed cuts. A blizzard fiercely streaked through Nixon Calhoon's headlight beam, as he drove blindly up the mountain. Only a few yards into Milepost 23, the snow stopped the train. Calhoon beat it back to town while he had the chance. A difficult daytime chore, cut-bucking was impossible at night. Then, Saturday, the rest of the railroad broke down. Two pulp cars jumped the rails and jackknifed, blocking the Holbrook line. Like the little train of the children's fable, the Breakthrough Special had to go to the rescue of a bigger train on the main line. Sunday--well, Sunday the sawmill superintendant, Jimmy Edens, looked at his log pond, as clear as a fish-bowl, and estimated he could saw lumber for only a few days longer. On Sunday a weary crew took the Breakthrough Special through the refilled cuts. Milepost 23 was cleared, Milepost 32. Milepost 37. At milepost 52 the front wheels rose on a plane of ice and left the rails. The remainder of the day was consumed in re-tracking the train, and bringing it back to McNary. "We've got to get through today," was the word from Mounes on Tuesday. "Take the two engines with the plows. Follow this with a third engine and forty cars, the log loader and caboose." "Yes, sir," said Trainmaster Ed Holland. His eyes were red from sleepless days over the dispatching desk. "One of these days we're bound to have some luck." Tuesday, indeed, the luck was better. The track was regauged at the derailment. The train moved downhill through aspen thickets, with the combined bulldozer force running interference through fallen rocks and felled trees. It took an hour to pass through Reservation Creek Canyon, with the crew watching for ice and rocks. Then, finally, the three locomotives, horns blatting, brought the cars and red caboose, symbol of Breakthrough success, into snowbound Maverick. The Little Train That Thought It Could, did. Yawning, blinking and grinning at the same time, Nixon Calhoon unhooked his radio microphone and called his boss, Syl Mounes. |

Blow-up of Arizona Highways 1971 Roadmap showing the Line.

hink you can make it over the mountain?" asked Sylvan Mounes.

"We'll try!" said Nixon Calhoon. Mounes had the courage of a

man who gave orders, and Calhoon the courage of a man that

followed them. And before their task was done, they would need

both kinds. Calhoon's assignment was plain enough: he was told

to almost-but God help him not quite-lose a quarter of a million

dollars in the wilderness.

hink you can make it over the mountain?" asked Sylvan Mounes.

"We'll try!" said Nixon Calhoon. Mounes had the courage of a

man who gave orders, and Calhoon the courage of a man that

followed them. And before their task was done, they would need

both kinds. Calhoon's assignment was plain enough: he was told

to almost-but God help him not quite-lose a quarter of a million

dollars in the wilderness.